‘There is no reason why skilled journalists should be employed for the purpose of communicating news to the Press. Plain statements of fact would suffice, and ordinary officials are surely competent to make them…nor will the confidence of independent organs in the Government’s news be restored by the knowledge that such news reaches them only after passing through a professionally staffed propaganda department.’

The Times of London criticises the British Government's attempts at news management, particularly its Public Information Branch in Dublin, March 1921.

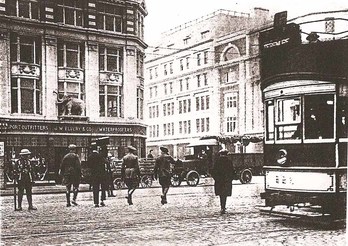

British soldiers arresting a photographer on the streets of Dublin, 1920 (Interim Report of the American Commission on Ireland, 1920). Journalists and newspapers suffered censorship, arrest, and intimidation throughout the war.

British soldiers arresting a photographer on the streets of Dublin, 1920 (Interim Report of the American Commission on Ireland, 1920). Journalists and newspapers suffered censorship, arrest, and intimidation throughout the war.

The Paper Wall: Newspapers and Propaganda in Ireland, 1919-1921 examines the role of the press in Ireland during these years. It also looks at the various means by which the British Government and Dáil Éireann sought to influence, censor, or otherwise control the press.

Chapter One - The British Government, Dublin Castle, and the Crown forces

The first chapter of the book deals with the relationship between the British Government, its administration in Ireland, and the press. This chapter is concerned not only with propaganda but also with how the Irish Administration and the Crown forces sought to influence, intimidate, or censor the press. Newspapers were initially subject to censorship, then suppression and prosecution. One internationally famous example happened in late 1920 when the owners and editor of leading Irish newspaper, the Freeman's Journal, faced a court martial. These Irish papers constantly risked intimidation and violent attack. Throughout 1920 and 1921 the Crown forces launched numerous attacks on press offices throughout the country. The chapter hopes to cast a new light on the attitude of the British in Ireland during 1919-1921.

The section on Basil Clarke's Public Information Branch examines Colonial Office files that have been open for around thirty years but which had not been fully employed in a study of this kind. This Public Information Branch was an attempt to manage the news through a system that Clarke termed ‘propaganda by news’. Ultimately, however, his system was not to succeed in the face of a distrustful and inquisitive press and because of debilitating divisions within the Crown forces and the Irish Administration. These divisions resulted in the Crown forces launching competing propaganda schemes, many of which were spectacular failures. These schemes, mostly concocted by a special section within the Royal Irish Constabulary, included the printing of fake versions of the republican Irish Bulletin as well as the creation of fake newspaper reports and photos of supposed 'battles' between the IRA and the Crown forces. The Paper Wall explains the complex relationship between the British government and the press in Ireland and examines the ramifications of this relationship for the Ireland of the time.

Eamon de Valera in the 1920s (US Library of Congress). After his return from the United States at the end of 1920, de Valera maintained a close watch on the Dáil’s ‘Department of Propaganda’. The department was managed by Desmond Fitzgerald until his arrest in February 1921, after which he was replaced by Erskine Childers.

Eamon de Valera in the 1920s (US Library of Congress). After his return from the United States at the end of 1920, de Valera maintained a close watch on the Dáil’s ‘Department of Propaganda’. The department was managed by Desmond Fitzgerald until his arrest in February 1921, after which he was replaced by Erskine Childers.

Chapter Two - Dáil Éireann and the Irish Republican Army

The second chapter deals with Sinn Féin and Dáil Éireann, their use of the Irish Bulletin and the relationship of republicans with the press in Ireland and foreign correspondents working in the country. Although Dáil and Sinn Féin propaganda was directed almost entirely abroad, Dáil members such as Michael Collins, Eamon de Valera, Desmond Fitzgerald, and Arthur Griffith were fully aware of the need to maintain a strong relationship with the Irish press. To this end, they facilitated the work of journalists as much as possible and they maintained close relationships with newspaper journalists working in the country.

This section of the book also examines the Dáil’s attempts to manage the press and journalists and considers why so much of its efforts were devoted to influencing journalists from outside of Ireland, especially through its famed propaganda newspaper, the Irish Bulletin. The book examines claims that republican propaganda was an untrammelled success and it seeks to place the publicity efforts of the Dáil’s ‘Department of Propaganda’ within the context of political and military developments within Ireland during the War of Independence. The Paper Wall shows how republicans sought to evade censorship, how figures such as Erskine Childers worked to put the Dáil Éireann case to journalists, and how the propaganda department of the Dáil compared with the British Public Information Branch in Dublin Castle. Ultimately, the book tries to asses how all these efforts influenced what appeared on the pages of daily newspapers in Ireland.

Chapters Three and Four - The Freeman's Journal and the Irish Independent

The third and fourth chapters study two national dailies, the Freeman's Journal the Irish Independent. These papers were widely read across the country and the chapters function as a case study of the nationalist press and its reactions to Dáil policies, IRA violence, Crown violence and British rule in Ireland during this time. These papers would play a vital role in Ireland during 1919-1921 and both, but especially the Freeman’s Journal, would regularly find themselves in confrontation with Dublin Castle and the Crown forces. These confrontations tell us much about British rule in Ireland and provide a fascinating study of how a government can seek to censor, manipulate, and intimidate a hostile press.

The second chapter deals with Sinn Féin and Dáil Éireann, their use of the Irish Bulletin and the relationship of republicans with the press in Ireland and foreign correspondents working in the country. Although Dáil and Sinn Féin propaganda was directed almost entirely abroad, Dáil members such as Michael Collins, Eamon de Valera, Desmond Fitzgerald, and Arthur Griffith were fully aware of the need to maintain a strong relationship with the Irish press. To this end, they facilitated the work of journalists as much as possible and they maintained close relationships with newspaper journalists working in the country.

This section of the book also examines the Dáil’s attempts to manage the press and journalists and considers why so much of its efforts were devoted to influencing journalists from outside of Ireland, especially through its famed propaganda newspaper, the Irish Bulletin. The book examines claims that republican propaganda was an untrammelled success and it seeks to place the publicity efforts of the Dáil’s ‘Department of Propaganda’ within the context of political and military developments within Ireland during the War of Independence. The Paper Wall shows how republicans sought to evade censorship, how figures such as Erskine Childers worked to put the Dáil Éireann case to journalists, and how the propaganda department of the Dáil compared with the British Public Information Branch in Dublin Castle. Ultimately, the book tries to asses how all these efforts influenced what appeared on the pages of daily newspapers in Ireland.

Chapters Three and Four - The Freeman's Journal and the Irish Independent

The third and fourth chapters study two national dailies, the Freeman's Journal the Irish Independent. These papers were widely read across the country and the chapters function as a case study of the nationalist press and its reactions to Dáil policies, IRA violence, Crown violence and British rule in Ireland during this time. These papers would play a vital role in Ireland during 1919-1921 and both, but especially the Freeman’s Journal, would regularly find themselves in confrontation with Dublin Castle and the Crown forces. These confrontations tell us much about British rule in Ireland and provide a fascinating study of how a government can seek to censor, manipulate, and intimidate a hostile press.

'I repeat that an organ, prohibited by law, which is used as the basis of propaganda and newspaper reports, and in which His Majesty's Government is condemned out of the mouths of those responsible for the murder campaign in Ireland, is not a document or propaganda that ought to be tolerated here. I say it is a tainted source.'

Hamar Greenwood, Chief Secretary for Ireland, criticises the Irish Bulletin newspaper in the House of Commons, 24 November 1920.

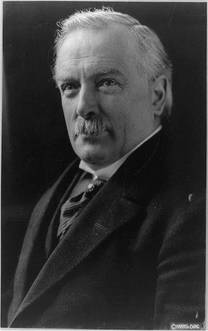

David Lloyd George, British Prime Minister, circa 1919 (US Library of Congress). His government had a fractious relationship with the press in Ireland and Britain during the War of Independence.

David Lloyd George, British Prime Minister, circa 1919 (US Library of Congress). His government had a fractious relationship with the press in Ireland and Britain during the War of Independence.

Chapters Five, Six, and Seven - the Cork Examiner, The Irish Times, and The Times

In the ensuing chapters three newspapers, the Cork Examiner, The Irish Times and the The Times of London are studied. The Cork Examiner was the most widely read regional newspaper and it provides an example of how both the British and republicans tried to control the news. The paper was suppressed by the military and suffered the constrictions of Martial Law. It was a nationalist paper yet it was a constant critic of IRA violence and, as with the Irish Independent, was attacked by republicans. The Irish Times, the most famous and widely read Unionist newspaper, provided a window into the minds of the southern unionist establishment. The paper was completely opposed to the aims of Dáil Éireann but a detailed study of the paper's editorials and reports reveals why, by 1920, the paper carried an editorial line that was strongly critical of the Irish administration and the British Government. Indeed, by the end of that year The Irish Times had reversed its previous policy and began advocating Dominion Home Rule for Ireland.

The Times of London also plays an important part in the book. The hostility of papers such as the Daily Mail, Daily News, and Manchester Guardian towards British actions in Ireland is already well known.The Times was one of the first English newspapers to grasp the importance of events in Ireland and it was The Times which was the first newspaper to advance detailed proposals for a settlement in Ireland. What was also interesting about The Times was that it was a long-time opponent of self-government for Ireland yet it completely reversed this policy during the War of Independence. Its reasons were not, initially, any new-found sense of affiliation with Ireland but a fear that Britain's standing would be damaged on the world stage, especially in the United States. Studying The Times also adds a wider dimension to the book in that English newspapers played a crucial role in Ireland during these years.

Ultimately, the newspapers were not merely recording events but were often active as participants, whether that was in their promotion of certain political agendas, their reporting of the key political and military issues or, as with the Freeman’s Journal and The Times of London, through their involvement in the political process that preceded the truce of July 1921. The Paper Wall explains the part played by the press in Ireland during a war in which it has been written that 'newspaper ink was spilled more freely than blood'.

In the ensuing chapters three newspapers, the Cork Examiner, The Irish Times and the The Times of London are studied. The Cork Examiner was the most widely read regional newspaper and it provides an example of how both the British and republicans tried to control the news. The paper was suppressed by the military and suffered the constrictions of Martial Law. It was a nationalist paper yet it was a constant critic of IRA violence and, as with the Irish Independent, was attacked by republicans. The Irish Times, the most famous and widely read Unionist newspaper, provided a window into the minds of the southern unionist establishment. The paper was completely opposed to the aims of Dáil Éireann but a detailed study of the paper's editorials and reports reveals why, by 1920, the paper carried an editorial line that was strongly critical of the Irish administration and the British Government. Indeed, by the end of that year The Irish Times had reversed its previous policy and began advocating Dominion Home Rule for Ireland.

The Times of London also plays an important part in the book. The hostility of papers such as the Daily Mail, Daily News, and Manchester Guardian towards British actions in Ireland is already well known.The Times was one of the first English newspapers to grasp the importance of events in Ireland and it was The Times which was the first newspaper to advance detailed proposals for a settlement in Ireland. What was also interesting about The Times was that it was a long-time opponent of self-government for Ireland yet it completely reversed this policy during the War of Independence. Its reasons were not, initially, any new-found sense of affiliation with Ireland but a fear that Britain's standing would be damaged on the world stage, especially in the United States. Studying The Times also adds a wider dimension to the book in that English newspapers played a crucial role in Ireland during these years.

Ultimately, the newspapers were not merely recording events but were often active as participants, whether that was in their promotion of certain political agendas, their reporting of the key political and military issues or, as with the Freeman’s Journal and The Times of London, through their involvement in the political process that preceded the truce of July 1921. The Paper Wall explains the part played by the press in Ireland during a war in which it has been written that 'newspaper ink was spilled more freely than blood'.

‘He is cynical and callous, brutally brusque and overbearing, and even where some occurrence is so horrible to be incapable of defence by him – and this is saying a good deal – he conveys the impression that Irish people, even women, deserve no consideration.’

The Irish Independent's view of Hamar Greenwood, Nov 1920. In the House of Commons, Greenwood routinely denied the reality of reprisals.

Return to The Paper Wall