John Boyle O'Reilly - from Ireland to Australia

The monument at O'Reilly's birthplace, Dowth (author).

The monument at O'Reilly's birthplace, Dowth (author).

From the Earth, A Cry follows O'Reilly's story from his birthplace of Dowth, County Meath, to his death in Boston during 1890. Here, I list the contents of From the Earth, A Cry and show how the various chapters highlight key aspects of O'Reilly's incredible life.

Chapter One - Early Life

O'Reilly was born near the Meath village of Dowth during 1844 to Eliza Boyle and William David O’Reilly. O'Reilly's father was a local national school teacher while Eliza managed an orphanage on the grounds of Dowth Castle, long-time home to the Netterville family. John’s parents were thus able to spare the family from the worst ravages of the Famine years. O’Reilly remembered his childhood as a happy time, although when an older brother became ill with tuberculosis the eleven year old John took a job with a local newspaper, the Drogheda Argus. It was the beginning of what would become an illustrious career as a journalist and, aged fifteen, he travelled to Preston, England, to work as a reporter with the Preston Guardian.

Chapter Two - Soldier

In 1863 O'Reilly returned to Ireland and volunteered for service in the British army, joining the Tenth Hussars, a cavalry regiment famed as ‘The Prince of Wales’ Own’ due to the presence of the future King Edward VII among its officers. The regiment was stationed in Ireland and O’Reilly was to spend much of his enlistment at Islandbridge Barracks (later known as Clancy Barracks) on the south bank of the River Liffey. The Irishman was a talented and popular soldier. ‘The best young soldier in the regiment’, declared one officer.

Chapter One - Early Life

O'Reilly was born near the Meath village of Dowth during 1844 to Eliza Boyle and William David O’Reilly. O'Reilly's father was a local national school teacher while Eliza managed an orphanage on the grounds of Dowth Castle, long-time home to the Netterville family. John’s parents were thus able to spare the family from the worst ravages of the Famine years. O’Reilly remembered his childhood as a happy time, although when an older brother became ill with tuberculosis the eleven year old John took a job with a local newspaper, the Drogheda Argus. It was the beginning of what would become an illustrious career as a journalist and, aged fifteen, he travelled to Preston, England, to work as a reporter with the Preston Guardian.

Chapter Two - Soldier

In 1863 O'Reilly returned to Ireland and volunteered for service in the British army, joining the Tenth Hussars, a cavalry regiment famed as ‘The Prince of Wales’ Own’ due to the presence of the future King Edward VII among its officers. The regiment was stationed in Ireland and O’Reilly was to spend much of his enlistment at Islandbridge Barracks (later known as Clancy Barracks) on the south bank of the River Liffey. The Irishman was a talented and popular soldier. ‘The best young soldier in the regiment’, declared one officer.

'I wrote these slips before I knew my fate, and I have nothing more to say, only God's holy will be done! If I only knew that you would not grieve for me I'd be perfectly happy and content'.

O'Reilly to his parents while awaiting his Court Martial, 1866

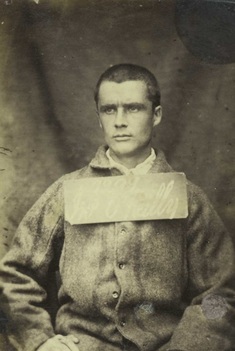

O'Reilly in Mountjoy Jail, 1866 (New York Public Library)

O'Reilly in Mountjoy Jail, 1866 (New York Public Library)

Chapter Three - Fenian

Unknown to his officer, O’Reilly became an active member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1865. That revolutionary group, more commonly known as the Fenians, was stealthily advancing its plans to overthrow British rule in Ireland. Its leader, James Stephens, had given a twenty-three year old Kildare man, John Devoy, the task of recruiting Irish soldiers in the British army into the Fenians. Through this work Devoy, who had spent a year in the French Foreign Legion and who had rapidly established himself as one of the foremost Fenians, made contact with O’Reilly, whom he described as ‘a handsome, lithely built young fellow’, and drew him into the planning of the rebellion. O’Reilly's role was to enlist soldiers into the Fenians, a task at which he was extremely successful. These men were to continue with their army duties but when the moment for action arrived, when the promised revolution took place, they were to join with the rebels. Yet O'Reilly's undercover work was exposed by informers and he was arrested during February 1866. During June and July 1866 O’Reilly was court-martialled in what was then the Royal Barracks, later Collins Barracks and what is now part of the National Museum.

Chapter Four - Convict

He was duly convicted of treason and sentenced to twenty years penal servitude. O’Reilly languished in Mountjoy Jail for nearly two months until, in early September 1866, he was taken back to the Royal Barracks to face his drumming-out ceremony. For the final time, he was dressed in his full military uniform and marched to the middle of the Royal Square. There, an officer affirmed O’Reilly’s guilt before the assembled soldiers and read aloud the sentence that had been handed down. Then, to the accompaniment of a slow drum beat, O’Reilly was stripped of his military uniform and dressed again in the uniform of a convict. With his military career forever finished he was shackled in chains and taken back to Mountjoy. O'Reilly would spend the next year moving through a succession of English prisons: Pentonville; Millbank; Chatham; Portsmouth; and the particularly degrading conditions of Dartmoor. He suffered the rigours of the silent and separate systems and made escape attempts from Chatham, Portsmouth, and Dartmoor. All ended in failure. But, just when he had resigned himself to a life of convict labour in Dartmoor, he heard news that of a convict ship destined for Australia.

Unknown to his officer, O’Reilly became an active member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1865. That revolutionary group, more commonly known as the Fenians, was stealthily advancing its plans to overthrow British rule in Ireland. Its leader, James Stephens, had given a twenty-three year old Kildare man, John Devoy, the task of recruiting Irish soldiers in the British army into the Fenians. Through this work Devoy, who had spent a year in the French Foreign Legion and who had rapidly established himself as one of the foremost Fenians, made contact with O’Reilly, whom he described as ‘a handsome, lithely built young fellow’, and drew him into the planning of the rebellion. O’Reilly's role was to enlist soldiers into the Fenians, a task at which he was extremely successful. These men were to continue with their army duties but when the moment for action arrived, when the promised revolution took place, they were to join with the rebels. Yet O'Reilly's undercover work was exposed by informers and he was arrested during February 1866. During June and July 1866 O’Reilly was court-martialled in what was then the Royal Barracks, later Collins Barracks and what is now part of the National Museum.

Chapter Four - Convict

He was duly convicted of treason and sentenced to twenty years penal servitude. O’Reilly languished in Mountjoy Jail for nearly two months until, in early September 1866, he was taken back to the Royal Barracks to face his drumming-out ceremony. For the final time, he was dressed in his full military uniform and marched to the middle of the Royal Square. There, an officer affirmed O’Reilly’s guilt before the assembled soldiers and read aloud the sentence that had been handed down. Then, to the accompaniment of a slow drum beat, O’Reilly was stripped of his military uniform and dressed again in the uniform of a convict. With his military career forever finished he was shackled in chains and taken back to Mountjoy. O'Reilly would spend the next year moving through a succession of English prisons: Pentonville; Millbank; Chatham; Portsmouth; and the particularly degrading conditions of Dartmoor. He suffered the rigours of the silent and separate systems and made escape attempts from Chatham, Portsmouth, and Dartmoor. All ended in failure. But, just when he had resigned himself to a life of convict labour in Dartmoor, he heard news that of a convict ship destined for Australia.

‘A rumor went through the prison…However it came is a mystery, but there did come a rumor to the prison, even to the dark cells, of a ship sailing for Australia! Australia! the ship! Another chance for the old dreams; and the wild thought was wilder than ever, and not half so stealthy.’

O'Reilly Describing the moment he realised that he was to be transported to Australia, 1867

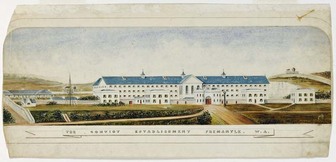

A contemporary sketch of Fremantle Prison (State Library of New South Wales). O'Reilly arrived at the Western Australian town of Fremantle in January 1868, although he would spend only a few weeks at the prison. He was then detailed to work in a road-building party near the town of Bunbury.

A contemporary sketch of Fremantle Prison (State Library of New South Wales). O'Reilly arrived at the Western Australian town of Fremantle in January 1868, although he would spend only a few weeks at the prison. He was then detailed to work in a road-building party near the town of Bunbury.

Chapter Five - The Hougoumont

By 1867 the process of transporting convicts from Britain and Ireland to Australia was almost at its end but O’Reilly would soon find himself among a group of Fenians aboard a ship travelling to Australia. That ship, which left England in October 1867, was the Hougoumont and it would prove to be the last vessel ever to transport convicts to the southern continent. The ship carried a convict population that was divided between the Irish Republican Brotherhood political prisoners and criminal convicts from British prisons. A few of O'Reilly's comrades kept diaries of the journey and the IRB prisoners even published a newspaper while on board, The Wild Goose. These documents provide us with a fascinating account of life aboard a convict transport.

Chapter Six - The Penal Colony of Western Australia

O’Reilly’s destination was what was then called the Penal Colony of Western Australia. To this day he remains a legendary figure in Western Australian history, almost entirely because he was one of the few convicts who escaped the colony. He was stationed in a convict depot near a coastal town called Bunbury, about one hundred miles south of the city of Perth. Most convicts in the colony were engaged in some form of land improvement and O’Reilly was part of a small group striving to build a road through the forest outside Bunbury. It was hard work but, in a chilling testimony to the brutality of the conditions within the English prison system, O’Reilly and his fellow Fenian convicts found their new life far preferable to their previous incarcerations in institutions such as Dartmoor. O'Reilly served his time under a warder named Henry Woodman, a humane man who effectively made O'Reilly his assistant. Yet O'Reilly's time in Western Australia would be marked by a failed love affair with the warder's daughter, Jesse Woodman. This relationship would brink O'Reilly to the brink of destruction.

Chapter Seven - Fugitive

O'Reilly's escape from Western Australia is the event that has, too often in later accounts, overshadowed the rest of his life story. It was daring escapade which suffered a series of unforeseen hurdles, including betrayal by what appeared to be his only means of escape. For two weeks the countryside around Bunbury was convulsed by a huge manhunt while O'Reilly was forced to hide amid the sand dunes of a deserted stretch of coastline. O'Reilly's salvation eventually arrived in the form of the whaling ship, Gazelle.

By 1867 the process of transporting convicts from Britain and Ireland to Australia was almost at its end but O’Reilly would soon find himself among a group of Fenians aboard a ship travelling to Australia. That ship, which left England in October 1867, was the Hougoumont and it would prove to be the last vessel ever to transport convicts to the southern continent. The ship carried a convict population that was divided between the Irish Republican Brotherhood political prisoners and criminal convicts from British prisons. A few of O'Reilly's comrades kept diaries of the journey and the IRB prisoners even published a newspaper while on board, The Wild Goose. These documents provide us with a fascinating account of life aboard a convict transport.

Chapter Six - The Penal Colony of Western Australia

O’Reilly’s destination was what was then called the Penal Colony of Western Australia. To this day he remains a legendary figure in Western Australian history, almost entirely because he was one of the few convicts who escaped the colony. He was stationed in a convict depot near a coastal town called Bunbury, about one hundred miles south of the city of Perth. Most convicts in the colony were engaged in some form of land improvement and O’Reilly was part of a small group striving to build a road through the forest outside Bunbury. It was hard work but, in a chilling testimony to the brutality of the conditions within the English prison system, O’Reilly and his fellow Fenian convicts found their new life far preferable to their previous incarcerations in institutions such as Dartmoor. O'Reilly served his time under a warder named Henry Woodman, a humane man who effectively made O'Reilly his assistant. Yet O'Reilly's time in Western Australia would be marked by a failed love affair with the warder's daughter, Jesse Woodman. This relationship would brink O'Reilly to the brink of destruction.

Chapter Seven - Fugitive

O'Reilly's escape from Western Australia is the event that has, too often in later accounts, overshadowed the rest of his life story. It was daring escapade which suffered a series of unforeseen hurdles, including betrayal by what appeared to be his only means of escape. For two weeks the countryside around Bunbury was convulsed by a huge manhunt while O'Reilly was forced to hide amid the sand dunes of a deserted stretch of coastline. O'Reilly's salvation eventually arrived in the form of the whaling ship, Gazelle.

'ABSCONDERS: John B. O'Reilly, registered No. 9843, imperial convict; arrived in the colony per convict ship Hougoumont in 1868; sentenced to twenty years, 9th July, 1866. Description - Healthy appearance; present age 25 years; 5 feet 7 inches high, black hair, brown eyes, oval visage, dark complexion: an Irishman. Absconded from Convict Road Party, Bunbury, on the 18th of February, 1869.'

A wanted notice in the Police Gazette, 1869

Return to From the Earth, A Cry