John Boyle O'Reilly - from Australia to the United States

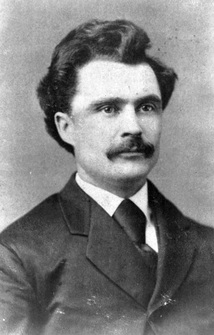

O'Reilly, circa 1871 (US Library of Congress). He became editor of The Pilot soon after joining the paper in 1870. It was only two years since he had escaped from the Penal Colony of Western Australia.

O'Reilly, circa 1871 (US Library of Congress). He became editor of The Pilot soon after joining the paper in 1870. It was only two years since he had escaped from the Penal Colony of Western Australia.

From the Earth, A Cry follows O'Reilly's story from his birthplace of Dowth, County Meath, to his death in Boston during 1890. Here, I list the contents of From the Earth, A Cry and show how the various chapters highlight key aspects of O'Reilly's incredible life.

Chapter Eight - The Whaling Ship

O'Reilly spent the next eight months hunting whales and he played a full part as a crew member aboard the Gazelle. He was nearly killed in one whale hunt, and almost recaptured by British forces on another occasion. The voyage was a profoundly important event in O'Reilly's life. Not only was he rescued from a life of convict labour but he made friendships aboard the vessel that would be of great importance to later events such as the Catalpa rescue. Finally, in November 1869, the ‘self-amnestied’ convict disembarked at the city of Philadelphia. Soon after, he travelled to Boston where he took a job as a reporter with The Pilot newspaper. One of his first stories for the paper was a report from the front lines of the latest of a series of Fenian attacks on Canadian territory during 1870.

Chapter Nine - The Pilot

The Pilot, founded in 1829, was well-established as one of the main Irish-American newspapers and its Cavan-born owner Patrick Donahoe had a reputation for hiring and promoting talented journalists. Even so, O’Reilly’s ascension within the paper was remarkable. By the summer of 1871, barely a year after joining the paper, O’Reilly had been made editor. O’Reilly thrived, both personally and financially, with The Pilot. He guided the paper through the destruction of its offices during Boston’s Great Fire of 1872 and through the depression that afflicted the United States after the financial crash of 1873. These cataclysmic events destroyed the financial empire of Patrick Donahoe and gave O’Reilly the chance to become joint owner of the paper, alongside the Archbishop of Boston John Williams, in 1876. The financial security which this afforded him meant that the formerly penniless convict was able to provide a comfortable life for his family. In 1872 John had married Mary Murphy, the ‘nicest girl in New England’ and together the couple would have four children. Between 1870 and 1890, The Pilot was to play the central role in the O'Reilly story.

Chapter Eight - The Whaling Ship

O'Reilly spent the next eight months hunting whales and he played a full part as a crew member aboard the Gazelle. He was nearly killed in one whale hunt, and almost recaptured by British forces on another occasion. The voyage was a profoundly important event in O'Reilly's life. Not only was he rescued from a life of convict labour but he made friendships aboard the vessel that would be of great importance to later events such as the Catalpa rescue. Finally, in November 1869, the ‘self-amnestied’ convict disembarked at the city of Philadelphia. Soon after, he travelled to Boston where he took a job as a reporter with The Pilot newspaper. One of his first stories for the paper was a report from the front lines of the latest of a series of Fenian attacks on Canadian territory during 1870.

Chapter Nine - The Pilot

The Pilot, founded in 1829, was well-established as one of the main Irish-American newspapers and its Cavan-born owner Patrick Donahoe had a reputation for hiring and promoting talented journalists. Even so, O’Reilly’s ascension within the paper was remarkable. By the summer of 1871, barely a year after joining the paper, O’Reilly had been made editor. O’Reilly thrived, both personally and financially, with The Pilot. He guided the paper through the destruction of its offices during Boston’s Great Fire of 1872 and through the depression that afflicted the United States after the financial crash of 1873. These cataclysmic events destroyed the financial empire of Patrick Donahoe and gave O’Reilly the chance to become joint owner of the paper, alongside the Archbishop of Boston John Williams, in 1876. The financial security which this afforded him meant that the formerly penniless convict was able to provide a comfortable life for his family. In 1872 John had married Mary Murphy, the ‘nicest girl in New England’ and together the couple would have four children. Between 1870 and 1890, The Pilot was to play the central role in the O'Reilly story.

'For all time to come, the freedom and purity of the press are the test of national virtue and independence. No writer for the press, however humble, is free from the burden of keeping his purpose high and his integrity white. The dignity of communities is largely intrusted to our keeping; and while we sway in the struggle or relax in the rest-hour, we must let no buzzards roost on the public shield in our charge.'

O'Reilly's speech to the Boston Press Club, 1879

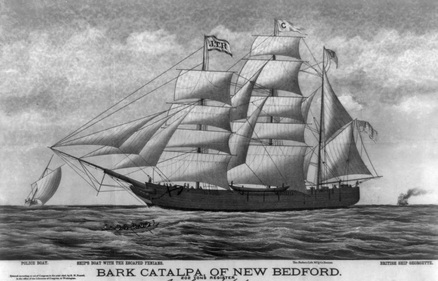

The events of John Boyle O'Reilly's escape, in 1869, from the Penal Colony of Western Australia are often confused with the famed Catalpa rescue of 1876. The Catalpa was an American Whaling ship which Clan na Gael employed to rescue six Fenian prisoners from Western Australia. John Devoy masterminded the expedition, although O'Reilly played an important role early in its planning (picture from the US Library of Congress).

The events of John Boyle O'Reilly's escape, in 1869, from the Penal Colony of Western Australia are often confused with the famed Catalpa rescue of 1876. The Catalpa was an American Whaling ship which Clan na Gael employed to rescue six Fenian prisoners from Western Australia. John Devoy masterminded the expedition, although O'Reilly played an important role early in its planning (picture from the US Library of Congress).

Chapter Ten - Civil Rights and Wrongs

O'Reilly took over as editor at a time of great rancour between the Irish and black communities. The two groups viewed each other with suspicion and the Detroit Plaindealer complained that the Irish were too quick to forget that they had been victims of prejudice writing that ‘almost their first Americanism' is ‘down with the Nagur’. There was more than a little truth in this statement and O’Reilly was to spend much of his time as editor disputing such attitudes, whatever their source. O’Reilly’s writings on this subject were not always welcomed by the subscribers to his paper. One of these readers, from Georgia, wrote to O’Reilly to condemn the editor for his support of race integration. The letter writer was especially dismayed by O’Reilly’s criticisms of the Franklin Typographical Society, an organisation which had recently refused admittance to a black man. These men, the letter-writer asserted, ‘have too much respect for their race to associate with Negroes’. O’Reilly was unrepentant and replied to the letter via an editorial: 'We are sorry that such sentiments should come from one who boasts of belonging to the ‘faithful Irish’. There is nothing Irish about his principles; and we are glad to receive the ‘stop my Pilot’ of such a man. We glory in the very things he hates…The Pilot holds that the colored man stands on a perfect equality with the white man.' This statement was to be a guiding principle of The Pilot under O’Reilly’s editorship and it was a principle that would similarly inspire him to defend Native Americans, Jews, and other beleaguered groups in the United States.

Chapter Eleven - The Queen's Prisoners and the King's Men

O'Reilly departed the Irish Republican Brotherhood after the failed attack on Canada in 1870. He became a critic of the group and of secret societies in general. Yet, he remained close friends with other exiled Fenians such as John Devoy and Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. Although O’Reilly’s condemnations of the Fenians were often controversial, his friendships with men such as Devoy served to protect O’Reilly from accusations that he was a turncoat. Also, although he never returned to Ireland, O’Reilly retained a strong commitment to Irish affairs and he would play a an important early role in the famed Catalpa rescue of 1876. Along with Devoy, O’Reilly helped to organise an expedition whereby the whaling ship Catalpa sailed to Western Australia and freed six Fenian convicts.

O'Reilly took over as editor at a time of great rancour between the Irish and black communities. The two groups viewed each other with suspicion and the Detroit Plaindealer complained that the Irish were too quick to forget that they had been victims of prejudice writing that ‘almost their first Americanism' is ‘down with the Nagur’. There was more than a little truth in this statement and O’Reilly was to spend much of his time as editor disputing such attitudes, whatever their source. O’Reilly’s writings on this subject were not always welcomed by the subscribers to his paper. One of these readers, from Georgia, wrote to O’Reilly to condemn the editor for his support of race integration. The letter writer was especially dismayed by O’Reilly’s criticisms of the Franklin Typographical Society, an organisation which had recently refused admittance to a black man. These men, the letter-writer asserted, ‘have too much respect for their race to associate with Negroes’. O’Reilly was unrepentant and replied to the letter via an editorial: 'We are sorry that such sentiments should come from one who boasts of belonging to the ‘faithful Irish’. There is nothing Irish about his principles; and we are glad to receive the ‘stop my Pilot’ of such a man. We glory in the very things he hates…The Pilot holds that the colored man stands on a perfect equality with the white man.' This statement was to be a guiding principle of The Pilot under O’Reilly’s editorship and it was a principle that would similarly inspire him to defend Native Americans, Jews, and other beleaguered groups in the United States.

Chapter Eleven - The Queen's Prisoners and the King's Men

O'Reilly departed the Irish Republican Brotherhood after the failed attack on Canada in 1870. He became a critic of the group and of secret societies in general. Yet, he remained close friends with other exiled Fenians such as John Devoy and Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. Although O’Reilly’s condemnations of the Fenians were often controversial, his friendships with men such as Devoy served to protect O’Reilly from accusations that he was a turncoat. Also, although he never returned to Ireland, O’Reilly retained a strong commitment to Irish affairs and he would play a an important early role in the famed Catalpa rescue of 1876. Along with Devoy, O’Reilly helped to organise an expedition whereby the whaling ship Catalpa sailed to Western Australia and freed six Fenian convicts.

'The border-cry of vengeance is heard already, and it is probable that an attempt will be made to extirpate the entire Sioux. But the day will come when these things cry to Heaven against the United States. The treatment of the Indians has been a red record of rascality and crime; and it is worse than ever to-day. The Sioux warriors did not murder Custer and his soldiers. They met him in a fair fight, out-generalled him, and cut him to pieces.

He tried to do the same to them.'

O'Reilly in The Pilot after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, 1876

Chapter 12 - Poet

Not only was John Boyle O'Reilly one of Boston’s foremost citizens but he was one of the most commercially successful writers of his time, producing four volumes of poetry and two novels. The novels, Moondyne and The King's Men were commercial successes and remain important texts in any study of O'Reilly. It was, however, O'Reilly's poetry which captured public attention during his life. He published four volumes: 'Songs from the Southern Seas'; 'Songs, Legends and Ballads'; 'Statues in the Block and Other Poems'; and 'In Bohemia'. Alongside the story of his escape from Australia O'Reilly's historical memory has been dominated by his poetry, or, it would be more accurate to say, a selection of his poetry. Poems such as 'A White Rose' were included in anthologies in the late nineteenth century and they remain popular today. His poems on social, economic, and political issues were forgotten soon after his death and remain largely unknown. Yet they remain key to any understanding of O'Reilly's personality and his beliefs. Those poems, along with his journalism, display a public figure far removed from the safely de-politicised dreamer that still emerges in some accounts of O'Reilly.

Not only was John Boyle O'Reilly one of Boston’s foremost citizens but he was one of the most commercially successful writers of his time, producing four volumes of poetry and two novels. The novels, Moondyne and The King's Men were commercial successes and remain important texts in any study of O'Reilly. It was, however, O'Reilly's poetry which captured public attention during his life. He published four volumes: 'Songs from the Southern Seas'; 'Songs, Legends and Ballads'; 'Statues in the Block and Other Poems'; and 'In Bohemia'. Alongside the story of his escape from Australia O'Reilly's historical memory has been dominated by his poetry, or, it would be more accurate to say, a selection of his poetry. Poems such as 'A White Rose' were included in anthologies in the late nineteenth century and they remain popular today. His poems on social, economic, and political issues were forgotten soon after his death and remain largely unknown. Yet they remain key to any understanding of O'Reilly's personality and his beliefs. Those poems, along with his journalism, display a public figure far removed from the safely de-politicised dreamer that still emerges in some accounts of O'Reilly.

'The men of the city who travel and write, whose fame and

credit are known abroad,

The people who move in the ranks, polite, the cultured

women whom all applaud.

It is true, there are only ten thousand here, but the

other half million are a vulgar clod;

And a soul well-bred is eternally dear – it counts

so much more on the books of God.

The others have use in their place, no doubt; but

why speak of a class one never meets?

They are gloomy things to be talked about, these

common lives of the city streets.'

O'Reilly's Poem, 'The City Streets'

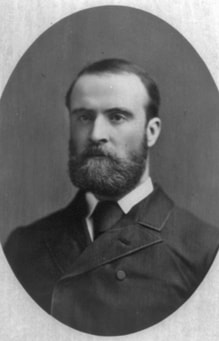

Charles Stewart Parnell during his visit to the United States in 1880 (US Library of Congress). John Boyle O'Reilly was part of the delegation which welcomed Parnell to the States.

Charles Stewart Parnell during his visit to the United States in 1880 (US Library of Congress). John Boyle O'Reilly was part of the delegation which welcomed Parnell to the States.

Chapter 13 - All Things Irish

Throughout his time with The Pilot O'Reilly devoted much his attention, and that of his paper, to Irish issues, both in the USA and Ireland. O’Reilly remained a friend of John Devoy and he worked closely with Michael Davitt and Charles Stewart Parnell as a leading member in the American wings of the Land League and Home Rule movements. He also sought to help integrate Irish immigrants into wider American society. A keen supporter of the Democratic Party, O'Reilly believed that ultimately the Irish in the United States must direct their energies towards their new home and 'become good American citizens'.

Chapter 14 - 'The Word Must be Sown'

O'Reilly remained active in a wide range of causes throughout the late 1880s and he devoted much of his paper’s reportage to the social and economic turmoil that he witnessed all around him. He continued his literary endeavours and even found time to write a manual on boxing, O'Reilly's favourite sport. Yet this blur of activity came to a sudden end in August 1890 when O'Reilly died aged forty-six. A few years after O’Reilly’s death Michael Davitt tried to explain why so many people were enraptured by the man from Dowth. The two men had remained friends up until O’Reilly’s death although, politically, they had taken different paths. Despite their differences Davitt spoke of a man who was; ‘handsome and brave, gifted in rarest qualities of mind and heart, broad-minded and intensely sympathetic, progressive and independent in thought, with an enlightened and tolerant disposition, in religion and politics, more in keeping with a poetic soul than with an ordinary human temperament.’ It was a fitting testimonial to a remarkable person.

Throughout his time with The Pilot O'Reilly devoted much his attention, and that of his paper, to Irish issues, both in the USA and Ireland. O’Reilly remained a friend of John Devoy and he worked closely with Michael Davitt and Charles Stewart Parnell as a leading member in the American wings of the Land League and Home Rule movements. He also sought to help integrate Irish immigrants into wider American society. A keen supporter of the Democratic Party, O'Reilly believed that ultimately the Irish in the United States must direct their energies towards their new home and 'become good American citizens'.

Chapter 14 - 'The Word Must be Sown'

O'Reilly remained active in a wide range of causes throughout the late 1880s and he devoted much of his paper’s reportage to the social and economic turmoil that he witnessed all around him. He continued his literary endeavours and even found time to write a manual on boxing, O'Reilly's favourite sport. Yet this blur of activity came to a sudden end in August 1890 when O'Reilly died aged forty-six. A few years after O’Reilly’s death Michael Davitt tried to explain why so many people were enraptured by the man from Dowth. The two men had remained friends up until O’Reilly’s death although, politically, they had taken different paths. Despite their differences Davitt spoke of a man who was; ‘handsome and brave, gifted in rarest qualities of mind and heart, broad-minded and intensely sympathetic, progressive and independent in thought, with an enlightened and tolerant disposition, in religion and politics, more in keeping with a poetic soul than with an ordinary human temperament.’ It was a fitting testimonial to a remarkable person.

'With his pen, John Boyle O’Reilly sent through the columns of a newspaper that he edited in this city words in our behalf that were Christian, and anathemas that were just. Not only that, but he went on to the platform, and, in bold and defiant language, he denounced the murderers of our people, and advised us to strike the tyrants back. It was a time when the cloud was most heavy, and more threatening than at any other period since reconstruction. At that time our Wendell Phillips was stricken by the hand of death, and then some doubted that they would be ever be able to see a clear sky. But in the midst of all the gloom we could hear Mr. O’Reilly declaring his determination to stand by the colored American in all contests where his rights were at stake.'

Speech by Edwin G. Walker following O'Reilly's death in 1890

Return to From the Earth, A Cry